The World and Us by R.M. Unger 2024

A brilliant philosopher. A meticulously crafted argument. An absurd and/or impossible conclusion. How can such a one go so wrong?

The heart of the book is how to live a better and spiritually richer life both as individuals and communities. Better here means more filled with “satisfaction of the spirit,” both for oneself and for those who live around us. The use of the term ‘spirit’ is somewhat ironic. Unger uses it a lot.

Unger tells us he is going to move us through the four core historical concerns of philosophy: ontology, epistemology, ethics, and politics. I don’t know why he left out aesthetics, but in reading the book, I see there was no particular room for it.

Ontology (what there is) and epistemology (in his view, “how we are to inquire”) are first up and essentially stage settings in the author’s program. We have a physical universe with a history. It has a beginning and in some distant future will have an end. Everything in it changes eventually. Even the cosmological constants, though stable for billions of years, will slowly change. Here’s the important part: there is no constancy anywhere, and there is no God (the reason his frequent use of ‘spirit’ is ironic). This means that in the end, not only are we—as individuals and as a planet—eventually all dead, but there is nothing else to which we move on. The good, the bad, and the ugly are all equalized [dead] by finitude sooner or later.

Nevertheless, during our lifetimes, we may strive to be “richer in spirit” and help those around us to be richer also—good karma for us—or not. We can attempt (not always successfully through no fault of our own) to lead more expansive lives and die only once, or we can not care, not try, lead trivial lives (more often, but again not always through faults of our own), and die many small deaths—I must admit I do not get this metaphor. Unger uses it many times. I’ll come back to it later.

Humans are both fully finite (when you’re dead, you’re dead) and transcendent (we have an inbuilt drive to exceed our limitations). Unger recognizes that the other animals do not share this inbuilt drive, and perhaps (he does not recognize) this is a clue to a reality he denies, but then again, maybe it is not. Possibly this part of us—the very notion that we can transcend our finitude—is an illusion. That some individual lives can be more valued (Mother Theresa) or condemned (Hitler) is undoubtedly not an illusion and not irrelevant to the lives of those humans who are contemporaries of the good or the evil. And so, Unger must focus on the point where the lives of contemporary human beings (and perhaps those of their immediate descendants) intersect.

And so he moves on to ethics in two broad domains, the “self-fashioned” life, and the life built around obligation to others—an ethics of connection. Throughout the middle of the book, Unger explores these two divergent ethical philosophies. Neither leads to an optimum, transcendent human life by itself, nor can they be fully amalgamated. Always, he says, there will be some tension between them. This tension is beneficial, a dialectic that allows lives to flourish in different ways.

After this, he arrives at his destination, politics, a topic that is never entirely out of the picture throughout the previous chapters of the book. His last chapter is the only part of the book where he makes concrete recommendations, and he makes many. About government, social service, education, and so on. What Unger is after here, reflected throughout the book, is what he calls the “near adjacent.” Near-adjacent refers to structural changes in the institutions of government and the political process that are incremental and not pie-in-the-sky utopian.

The near adjacent is not the same as changes within the context of the existing system that, otherwise, don’t change very much, for example, increasing (or decreasing) welfare payments, or changes in the tax code. Unger is referring to structural changes, albeit small at first, to the form of government itself. An example might be a direct popular election of the president (without the Electoral College) or some form of proportional representation in the Senate.

Unger’s goal in all of this is to enhance (what he calls “raising the temperature”) our democracy and deepen our freedom by making both the self-fashioning and connection ethics more supportable and mutually reinforcing. For example, his very first suggestion—getting big private money out of American political campaigns (i.e., overturning Citizens United, among other sensible recommendations)—is something already favored by 75% of the voting population of the United States, yet it does not happen. Why?

Here is why: Despite his “everything changes sooner or later” mantra—which may be technically true—one thing does not change quickly enough to make possible what he calls the “near adjacent,” and that is human nature. Once the rich and greedy have power, they are not going to let it go without a fight. As long as the not-yet-rich but ambitious are allowed to strive for power, they will do so. Once an elite is in control of some relatively stable structure, they will resist any such changes as Unger envisions.

Unger aims at a political and economic structure that is amenable to change, evolution, and experimentation, without such change having to be precipitated by crisis, which (as Slavoj Zizek has pointed out) is usually “violent and bloody.” But any change, no matter how beneficial to the majority now or in the long run, will always diminish those who now control the levers of power, even if the “diminishment” is merely some incremental reduction in their fabulous wealth.

Since, in the present circumstances, it is that fabulous wealth that secures the present power of the elite, what Unger suggests is, until some crisis brings the whole edifice down in some blood bath, simply utopian dreaming, notwithstanding Unger’s denial of that fact. In short, I applaud almost everything Unger recommends, but I am very skeptical that it can or will ever be possible, short of bloody revolution.

Up to this point, Unger is brilliant if utopian. When he expands his view from the nation to the world, he goes terribly wrong. What he wants, globally, is to maximize cultural diversity and minimize war, especially war between the “great powers,” whomever they might be at the time. However, he then goes on to say that the latter must not be purchased at the price of a world government, because that would compromise the diversity requirement. Here, his powerful intellect has utterly failed him. It is, perhaps, the one point on which I could debate him and win.

A world of armed states, such as we have now, will never remain without large-scale war for long. Global resources are always limited. No power ever has enough. So long as these states are individually armed, some power will decide that getting what it needs or merely wants is worth the price paid in blood—theirs and their neighbors. Unless the militaries of the world are under the command of a single entity, war is eventually inevitable. Leagues of nations (that he recommends) are never enough. If all or even some of the nations in the league are armed, there will always come a time when withdrawing from the league and waging war will appear to be a viable option.

Unger thinks treaties will do the job. In the absence of a world government, who will enforce the treaty if a powerful armed state elects to violate it? In theory, other nations, acting in concert, could intervene. The Europeans might have intervened to stop Hitler in the mid-1930s, or, for that matter, Russia in the twenty-first century, but that never happened because no one wants to go to war based on what the other side might do until they do it. When Germany invaded Poland, the other Western European powers declared war on Germany. In today’s nuclear age, even Russia’s outright invasion of a European country didn’t trigger that response. Unger offers no suggestion here. Treaties and leagues are never enough.

My second point concerns diversity. Unger does not seem to grasp that what most influences cultural diversity is not politics but geography (I recommend he read Robert Kaplan’s The Revenge of Geography to establish and solidify this point in his mind). Geography does not determine the specifics of culture, but it does shape its broad outlines. The people of two different desert lands will have different cultures. Still, those differences will contrast with the cultures of forest peoples, and they, in turn, will differ from the cultures of plains people or sea peoples, and those from the culture of mountain people, and so on. A world government will in no way flatten cultural differences, as Unger believes. How can a philosopher of Unger’s caliber not recognize that geography has more influence on culture than the political arrangements of a territorial State? Geographical differences will inevitably lead to cultural differences.

Finally, a “world government” does not entail or even imply a literal single political entity throughout the world any more than the United States Federal government means there are no individual (and varying) State governments. They, in turn, devolve power to local governments, and so on. Nor does “world government” imply or entail an autocracy or dictatorship. There is no reason the world government, in the long run, should not be democratic.

The primary role of a world government is to regulate global trade—governing the allocation of resources—and maintain firm control over any significant military power. Eventually, when the local, regional, continental, and provincial governments become accustomed to the situation, the military will, in fact, wither away, as there will be no one left to fight. Each State of the U.S. governs itself in its own way, but none seriously contemplate invading a neighboring State. At the same time, the Federal government has not maintained this peace through the threat of arms since the American Civil War. A global government is the only way to end war, whether global or otherwise, permanently. It will also save and put to productive use trillions of dollars now spent wastefully on national militaries.

There is an aspect of Unger’s economic views to which I’d like to draw attention. Throughout the book, Unger frequently mentions what he refers to as the growing “knowledge economy.” He never gets specific about what this actually means. Obviously, it includes computers, robots, and AI, but nowhere does he specify exactly what this means for the work of the world, except to declare that the future of human “deep freedom” depends on humans not performing tasks that machines can do. The problem is that machines will soon be able to do just about everything, from constructing our dwellings to making our clothes, growing, harvesting, and transporting our food, producing our energy, and so on. Machines can repair other machines when they break down. What are we all to do?

Unger gives us a few clues in his section on education. Some work will always be better with a human touch, even if machines can assist in it. For example, caregiving for the elderly, the lonely, the sick, and small children should be something everyone learns to do, literally as part of their middle and high school curriculum. Such an education would increase the amount of compassion in the world, and, of course, some will move on to become professional caregivers in the broader medical field—nurses, doctors, counselors, and so on.

Teaching might be another area that benefits from a human touch. We should encourage students to practice what they learn by teaching others. Middle schoolers teach primary schoolers, high schoolers teach middle schoolers, and so on, but always with professional help and supervision. We will surely need many experienced teachers.

Freed from labor, most humans today choose to consume and not create. A population freed from labor that machines can perform will consume resources even faster than we do today, given the leisure we have. Of course, a new educational regime can make a significant difference. Unger, in his last chapter, makes some good suggestions—see above—perhaps, over generations, humans can be persuaded to create rather than consume. However, on what basis will the creations be valued?

Finally, I want to address his “many small deaths” metaphor. It makes no sense to me, but Unger does suggest a comparison between a life that is trivial or wasted and one that is not. But who is to judge? Thanks to his ontological stipulations, a person who metaphorically slaves for “the man” all their life, perhaps does nothing else but read trashy novels before bed, and dies childless, has led a trivial life. But according to his ontology, Mother Theresa, Hitler, and the wage slave who makes no additional contribution to humanity are now equally dead. To be sure, some lives do much more good for humanity than others, but doing “more good” cannot be synonymous with “non-trivial.” Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong surely did not live trivial lives. Did they die only once? Are their lives something to which I (or anyone) should aspire?

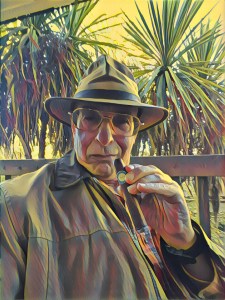

What about Unger himself? He writes philosophy books. I’ve written philosophy books. If his life is non-trivial, is mine? Of course, Unger is read more than I am, but why should that be a criterion? More people have read Mein Kampf (Hitler) than Unger, and Fannie Hill (Cleland) more than all of us put together. What about matters of opinion where Unger is plainly wrong and I am right, as in the business of “world government” above? Does that make my life non-trivial?

Politics, except during revolutions, changes more slowly than the span of a human life, but geography outlasts both by millennia. How can he have missed the truth that, without God (and not merely institutional religion — imperfect and corrupted like any other human institution) providing an unchanging moral compass, slowly changing human nature will never permit political evolution along the lines he envisions, short of the crises he abjures? Even if there is a God, such a change in human nature as Unger requires might need another few thousand years (we will no longer be around, but that is another matter), but it would mean that Mother Theresa and Hitler, both mortally dead, would no longer be equivalent. Isn’t that how we want our moral judgment to come out?

There is much more in this tome than I have addressed. For example, Unger tells us several times that altruism is not love, but if “Love is the desire to do good to others” (The Urantia Book), then sometimes altruism is love. The World and Us is an excellent piece of writing, possibly a magnum opus. Take it with a grain of salt.